EYE TO EYE WITH THE BROWN HARE

Interview with Barb Macek

Barbara, you have studied the Master Program with Art & Science and continued studying for a doctorate in philosophy with Virgil Widrich as your supervisor. What were your topics?

Dissertation Autoimmunität und Anthropologische Differenz - Hardcopy can be borrowed from Art & Science Library.

After completing my Master's degree in Art & Science, I continued my studies at the University of Applied Arts and graduated

in February 2024 with a doctorate in philosophy. The dissertation was a continuation of the research that began with my master's

thesis and was funded by the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

I’m currently in the process of developing a research project that will be an extension of my studies in the field of autoimmunity

and autoimmune diseases, involving collaborations and a long-term work plan. In parallel, I'm pursuing a project based on

my experiences of living in the countryside and my observations of the local wildlife.

Do you rather work in collectives or alone?

Since the beginning of this year, I have been working on a team-based project, where the aim is to build a team around a work concept that is being created at the same time. It's a very exciting process and a lot is already happening, just through discussions with the (future) collaborators.

Where do you find inspiration?

Sources of inspiration can come from almost anywhere; one thing that always has a positive effect on me is walking in the

countryside, up the cellar lanes and through the vineyards, listening to the birds and watching the hares running across the

fields.

Especially when I'm stuck or facing a problem, it often helps to just walk and talk to myself – I call it walking thinking

– ‘Gehdenken’. My brain is stimulated, the environment brings fresh perspectives, and when I return, the work can be continued

at a new point, or a new perspective opens up that sets a change in motion.

Would you like to tell us on what project you are currently working on? How you’ve started, what brought you there?

With the main building came two old wine cellars and a piece of wilderness next to the second wine cellar, which I have transformed into a place for birds – with nesting boxes, feeding stations, drinking and bathing facilities and, most importantly, hiding and resting places provided by the surrounding thicket.

The cellar lane leads through vineyards up a hill with a forest; on the other side of the hill there are more vineyards until you reach the next group of wine cellars. The vineyards are the habitat of the brown hare, but you can also spot red deer, polecats, badgers, (ground) squirrels and an impressive variety of birds.

Can you tell us more about this mind-set, and what do you mean by resonance?

The concept of resonance goes back to Romanticism and has been taken up more recently by Hartmut Rosa, who adapted it for

sociology. The practice I’m developing seeks to enable and capture the resonance between wild animals and humans. First of

all, it requires something like a fine-tuning of the senses, of all our receptors, a fine-tuning to be able to receive the

signals that wild animals send to us.

The mindset I mentioned, or the attitude that is required if you want to enable this kind of resonance, is characterized by

openness, calmness, attentiveness – and kindness. By the latter I mean a welcoming attitude or posture, informed by a basic

gratitude for the hare, the deer, the rabbit crossing your path. This can be expressed by performing an 'inward bow' as an

inner gesture of respect and appreciation, conveying this gratitude to the ground squirrel, the pheasant, the falcon for being

with you at this particular moment in space-time.

If you are able to create a situation in which curiosity overcomes fear – so that the hare becomes curious enough to stop,

to pause, to look at you – then you are already entering the second phase of the encounter, where you are opening up a space

in which glances can be exchanged as a means of exploration and contact, a space in which resonance can emerge.

What do you want to achieve with the project, what’s special about it?

My aim with this project is to develop a practical and theoretical framework that can be shared and reproduced in the context

of interspecies encounters. In the long run, I am aiming for a transformation – a real change in interspecies relationships.

Can you already say something about the outcome of your project?

There is this conglomerate that appears for a moment during these encounters, I call it ‘encounter figure’, it is the figure

of me and the hare in this very specific moment in space-time – my eyes meeting the hare's eyes, the hare's ears pointing

in my direction; it is attention, awareness, a moment of total presence. And it is also the point at which research and artistic

practice converge: I experience the resonance and at the same time I make inner notes about what is happening, about what

I am perceiving. Shortly after the encounter, as soon as possible, I record these notes.

The transcripts of these recordings will allow for a systematic analysis as well as for poetic interventions. This is the

investigation at the level of language, one possible outcome being a series of poems.

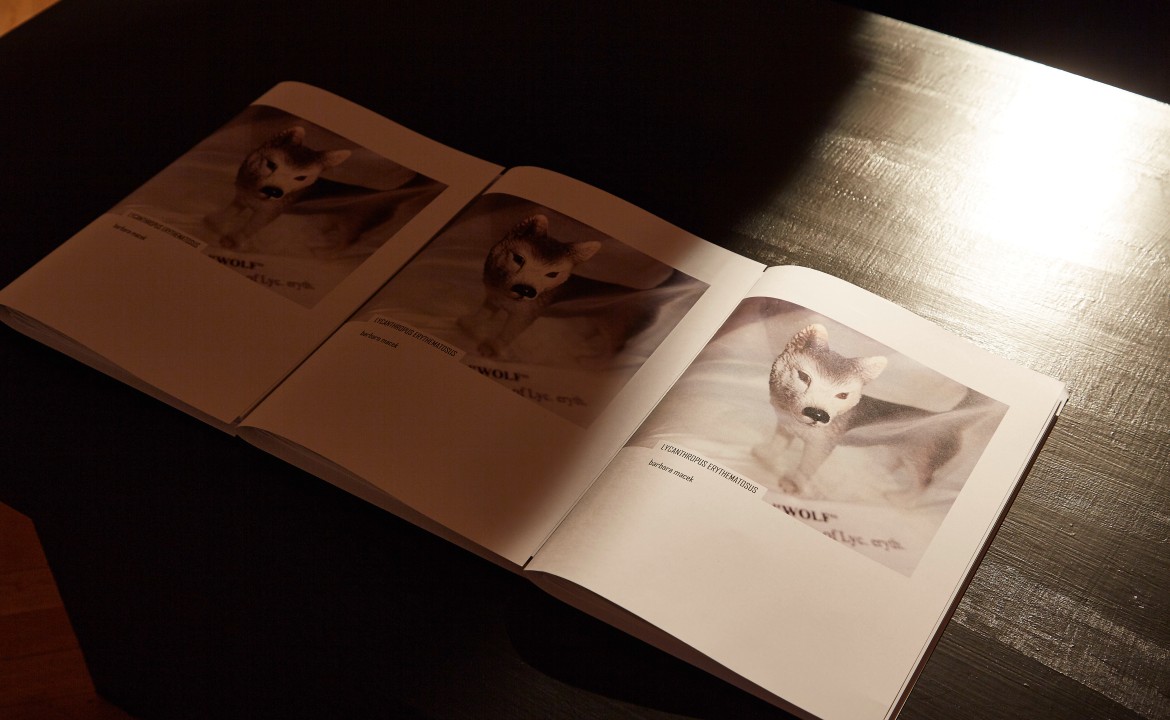

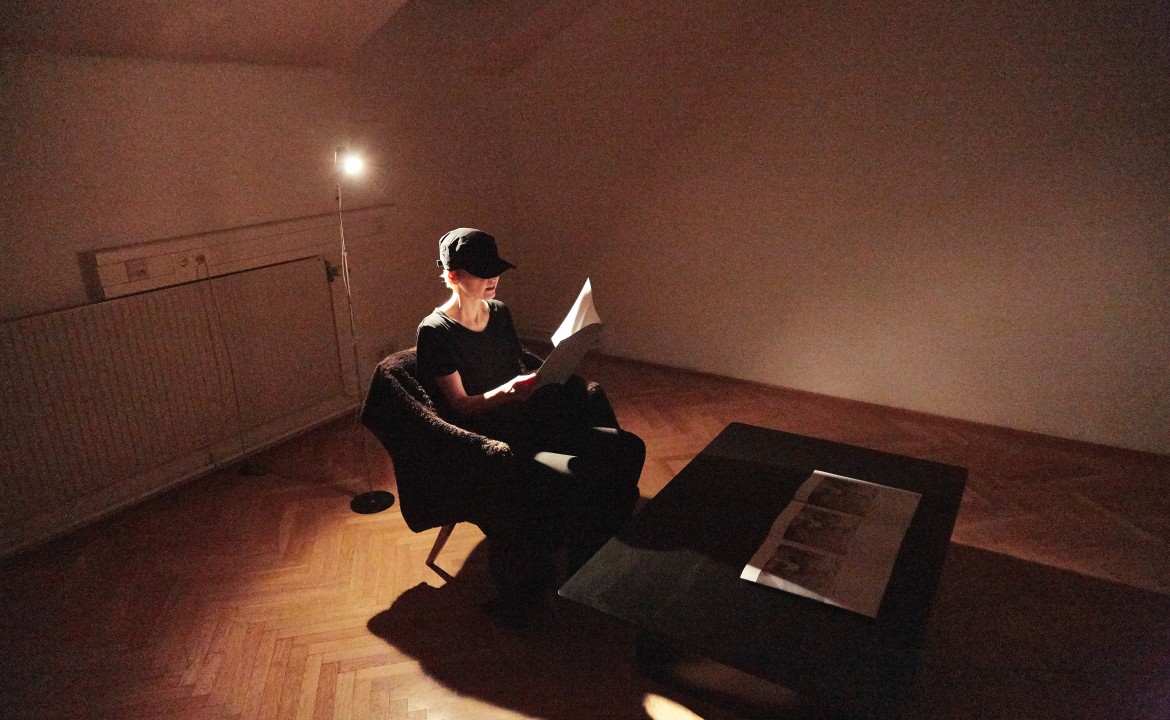

There is also another level of artistic research involved, a photographic inquiry. It begins with the attempt to capture the

encounters with my camera. The resulting photographs become the basis for collages, superimposed images of moments of resonance,

which offer an approach to manifesting these fragile, transient figures of the encounter on a visual level, thus making them

tangible, communicable and, last but not least, explorable.

The images that are part of this interview are examples of the project's photographic research.

Why did you choose Artistic Research as your field of work?

It has to do with the main drive or basic motivation for my work, which is almost always linked to a pressing question that

arises. It’s the urge to understand something, to get to the bottom of something, like the mystery of autoimmunity.

What I find particularly attractive about AR is its transdisciplinarity, that it is not bound to one discipline and its rules.

This freedom is very important to me, this openness that allows me to include the most diverse – even contradictory – positions

in my research, thus taking into account the complexity of issues arising from the diversity of challenges we face today.

As an artistic researcher, I am free to look into different schools of thoughts and mentalities, into natural sciences, humanities,

into literature, poetry at the same time; I can pick up useful instruments or approaches without being limited to the (methodological

and theoretical) boundaries of one discipline.

AR can also mean research creation, where you develop your own methodology, your own research instruments or use given instruments

in a new way, including artistic means and media. I’m convinced that If you really want to find out something new, you have

to do something new.

This sums up what artistic research can do – and what it means to me, so probably it’s a good closing line.

Thank you, dear Barbara for this interesting insight in your life and work.

BARB MACEK

Interview: Gerda Tschoerdy Fischbach, March 2025